The Mid-Town Journal chronicled the home addresses of hundreds of LGBTQ+ Bostonians from 1938 to 1966. As previously stated on the General Findings page, the vast majority of queer and gender non-conforming folks lived in four specific neighborhoods which were the South End, Back Bay, Beacon Hill, and Roxbury. The South End was four times more popular for LGBTQ+ to live compared to the other three neighborhoods.

Using apartment blueprints found within the Boston City Archives, focusing on Back Bay, the South End and Beacon Hill, this page will highlight the specific living arraignments and circumstances that many gay Bostonians faced in the mid-twentieth century. For example, wealthier gay men were able to afford the more spacious and well-kept houses in the Back Bay while poorer transgender women and gay men of color were relegated to the more economically disadvantaged neighborhood of the South End.

Back Bay

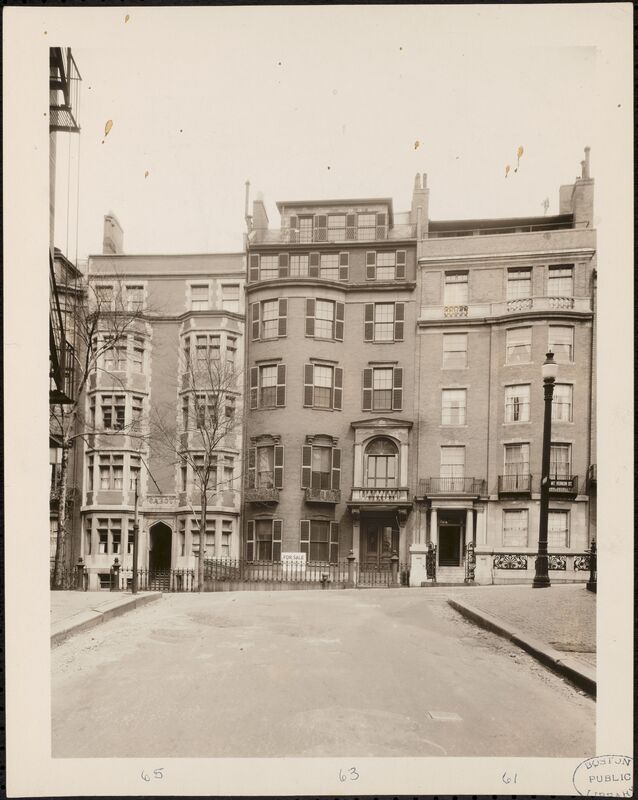

The Back Bay neighborhood is a relatively newer part of Boston built upon a landfill. Its construction began in 1859 because there was a demand for additional luxury housing. The architect of Back Bay was Arthur Gilman who modeled this new section of the city after Parisian boulevards with wide open streets and a tree-lined mall. Soon after, cultural institutions of Boston began to move to Back Bay such as the Boston Society for Natural History and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. By the end of the nineteenth century, Boston's most elite and rich citizens such as "novelist William Dean Howells, painter John Singer Sargent, art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner and financier Abbot Lawrence" called Back Bay home.1 By the 1950s, many Back Bay residents were fleeing to the suburbs for larger homes and spacious yards. Yet, the Back Bay neighborhood continued to be bastion of elegance and wealth well into the twenty-first century. As of 2021, the median price of a home in Back Bay was $1,299,000.2

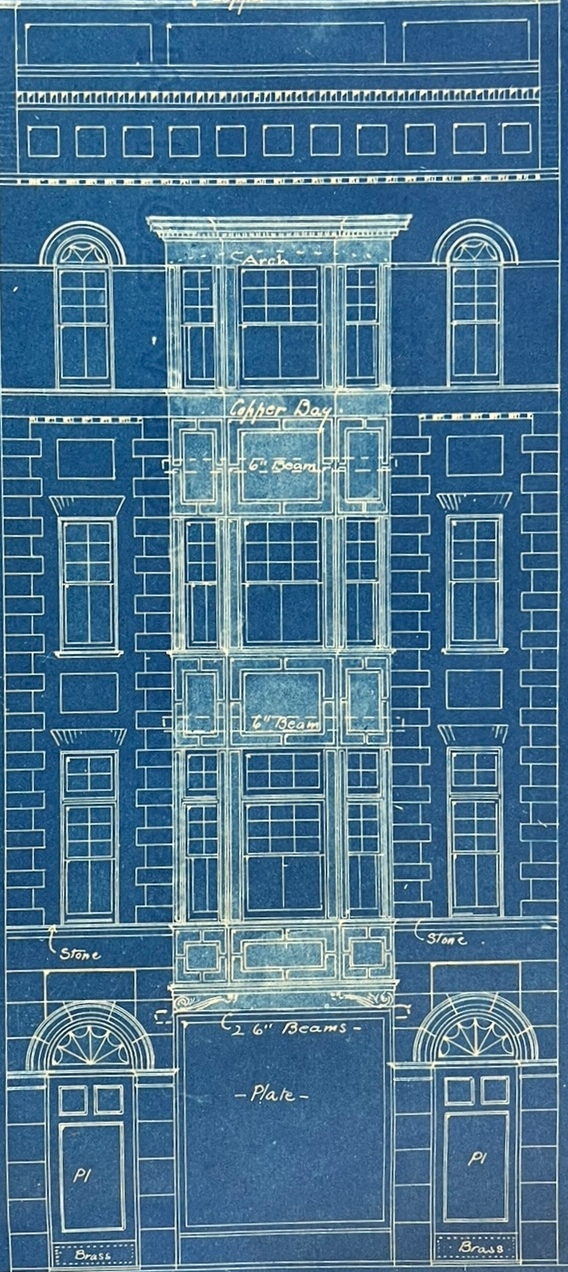

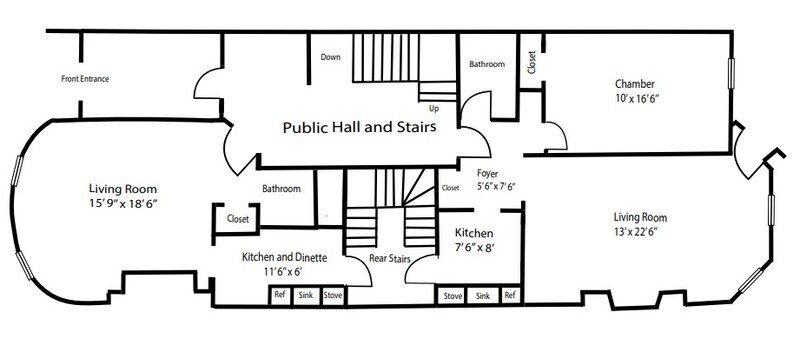

Living in the prestigious Back Bay neighborhood of Boston certainly offered a highly sought-after location, but it came with certain limitations, particularly when it came to living space. As depicted in the layout provided, apartments in the area, particularly on Beacon Street, followed a common pattern. On the first floor, a typical apartment was divided into two separate units. The first unit, located closest to the front entrance, was a modest one-bedroom, one-bathroom studio apartment, encompassing approximately 400 square feet of total space. This size suggests that it would have been suitable for an individual looking for a compact living arrangement. The second unit, situated further away from the front entrance, offered a bit more space, constituting a two-bedroom, one-bathroom layout with around 550 square feet. This configuration could comfortably accommodate at least two tenants, making it a more attractive option for gay men or transwomen wanting to live together.

Though not shown, the apartments on the second and third levels enjoyed slightly more space, as the absence of a front entrance on those floors allowed for additional square footage. These apartments had similar floorplans to the two-bedroom, one-bathroom unit of the first floor. This likely provided a bit more comfort and flexibility for residents on those levels. This spatial distribution highlights the challenges of space optimization in a prestigious and high-demand area like the Back Bay. While residents enjoyed the prestige and convenience of living in one of Boston's finest neighborhoods, they had to contend with limited living space, especially on the lower floors. However, the layout's compactness also emphasizes the efficient use of available space, reflecting the architectural considerations of the time.

Moreover, it is important to highlight that the smaller size of the apartments on the first floor could have been a more budget-friendly option for specific residents or individuals who preferred a prime location, but didn't necessarily need a large living space. Conversely, the larger two-bedroom unit on the first floor and the apartments on higher levels might have demanded higher rental prices. These units would have likely catered to those who were willing to pay a premium for more spacious accommodations and increased privacy. Such privacy and space would have been particularly valuable to gay men and transwomen who desired to live more openly at home without the concern of prying neighbors or nosey police officers looking through the windows.

Further examination has also revealed a fascinating portrait of the LGBTQ+ individuals who were living in these Back Bay apartments. The findings indicated that 80% of the queer and gender non-conforming individuals in this area were identified as gay cis-gender men, with the remaining 20% comprising of transgender women. Apartment listings from the late 1940s and 1950s revealed a wide range of rental costs, typically ranging from $55 to $105 a month.3 These figures were substantially unaffordable for the average blue-collar worker in Boston during the 1950s, as their earnings often fell below $100.4 While the journal does not explicitly disclose the occupations of the queer and gender non-conforming individuals of the Back Bay, it is reasonable to surmise that a significant portion of them likely held relatively well-off and financially stable jobs. Many may have worked in clerical or professional and technical roles, which were among the highest paying and most respectable professions of that era.

However, it is essential to acknowledge the type burden of renting these apartments would have presented for transgender women. To afford the monthly rent, many of them may have felt compelled to conceal not only their sexual identity, but also their non-conforming gender identity at work and in public in fear of losing their jobs or harming their professional reputation. Contrasted with gay men, who were not burdened by the same need of this dual concealment in their daily lives.

Lastly, all 22 of the gay men and transgender women mentioned in the journal, who resided in Back Bay, were white. Strikingly, there were no records of black queer men or transwomen living in the area at that time. Boston did not have the racial segregation laws similar to those found in the American South; there were other significant factors at play, effectively barring African Americans from accessing Back Bay properties.

High rental costs, discriminatory redlining practices, and pervasive racism in Boston hindered African Americans from securing well-paying jobs that would have provided them the means to afford these expensive rentals. As a result, black queer Bostonians were effectively pushed to seek housing in other neighborhoods like the South End and Roxbury, where living costs were relatively more affordable and where a larger black community had already established itself. The historical context reveals how racial and economic barriers intersected to perpetuate residential segregation and restrict opportunities for marginalized communities in the city.

South End

The South End, like Back Bay, was built upon a landfill that was originally marshland in the late 1840s. Before Back Bay's inception, the South End was a neighborhood populated mostly by white middle and upper class folks through most of the first and second half of the nineteenth century. The exodus of wealthy native born white families began with the Great Boston Fire of 1872, the financial Panic of 1873, the influx of European immigrants in the latter half of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century and the development of the Back Bay.

The Great Boston Fire of 1872 destroyed the warehouses and commerce that many families depended upon while the economic downturn a year later diminished any remaining business prospects left. As a result, wealthy families began to move out the South End and into the relatively new and affluent Back Bay or to the suburbs of Boston.5

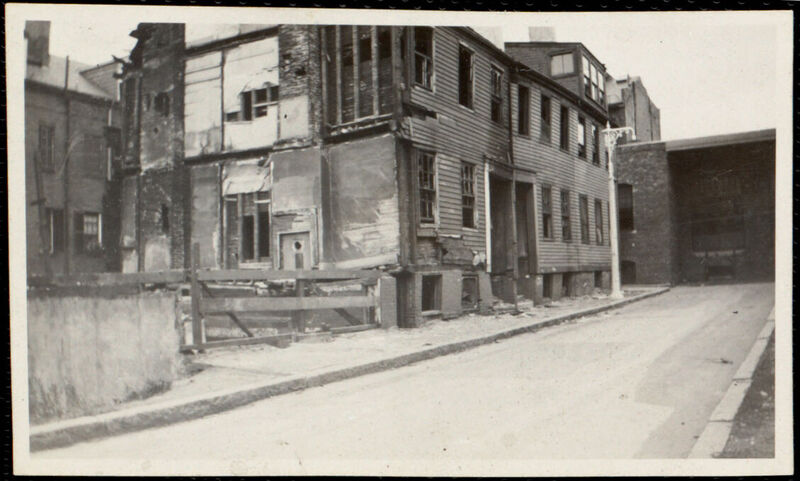

With the exodus of many wealthy families, poor southern and eastern European immigrants began to occupy the neighborhood. Homes that were once inhabited by a singular middle or upper class family were now converted into tenements and lodging houses that would home several families at a time. By the end of the nineteenth century, the South End was home to a diverse poor immigrant working class community of Jews, Italians, Syrians, Greeks, Armenians and later African-Americans from not only Jamaica and Barbados, but also from the American south.6

By World War Two, poverty and divestment had taken its toll on the South End. Many of its homes began to deteriorate and were condemned by the city. By the late 1950s, the city of Boston demolished over twelve city blocks of the South End under its urban renewal program, ultimately displacing over a thousand residents.7 Cheap housing continued to dominate the South End until the 1970s when gentrification and new revitalization projects began to drive low-income white and black families and immigrants out of the neighborhood.

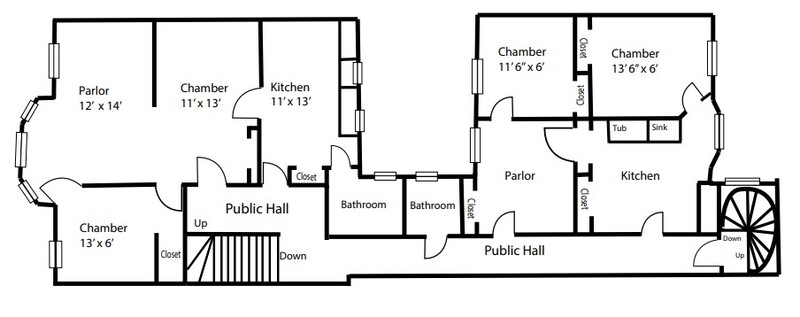

Pictured above is a typical home found not only on Tremont Street, but in most of the South End. As we can see, like the house in Back Bay, this particular apartment is split into two units. This layout is of the second floor. The third and fourth floors were identical to the second. Though, the first floor is not shown, it would have had a similar layout except for a slightly smaller living space to accommodate the front entrance. Both have two bedrooms, a parlor, a kitchen and single bathroom. Each united had approximatly 550 square feet of living space. With its particular set up, there would have most likely been at least two individuals living in each unit.

Compared to the very high monthly rent in the Back Bay, the South End was much more affordable, especially for lower income LGBTQ+ Bostonians. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a four room apartment in the South End, similar to the 635 Tremont Street location, would usually be advertised for as low as $11 a month to high as $39 a month.8 Living with multiple roommates would mean that the average renter would only be paying around $10-$15 a month for rent. Considerably lower than what renters in Back Bay were paying. Additionally, with the South End being a neighborhood that housed many working-class low income families and individuals, their weekly salary would have been enough to cover such an expense. For example, many poor working class women would have made around $120 a month before taxes and men would have made around $160 a month before taxes which would have made a South End apartment affordable especially with roommates.9 The demographics of the South End were much more diverse than Back Bay and the reports from The Mid-Town Journal confirmed that. The South End was not only a haven for southern and eastern European immigrants, but also for native and immigrant blacks. By the 1950s, Boston had a black population of about 50,000.9 The black community was mostly concentrated in the South End, Dorchester and Roxbury.10

Not only was the white gay and transgender population visible, but so was black queer population. For example, through the paper and in conjunction with census records, I was able to identify a total of 12 white and 10 black queer and gender non-conforming individuals living in the South End in the 1940s and '50s. Of that cohort, six folks were black transgender women and four were white transgender women. The rest were cis-gender black and white gay men.

When compared with the demographics of other Boston neighborhoods, the South End was much more diverse and inclusive. Black and white transwomen walked the streets and felt comfortable enough presenting themselves in public (even with the risk of violating cross-dressing laws) as so did the gay male population. Russ Lopez noted that by the 1950s, the South End, with its cheap housing and proximity to LGBTQ+ bars, hotels, cafés, was quickly becoming a popular neighborhood for transgender women and some gay men.11 But, as my research shows, the South End was already becoming a haven for many poor black and white transwomen and gay men as early as the beginning of the 1940s. Compared to the rest of the city, the South End appeared as more of an equitable neighborhood, due mostly to its cheap and decrepit housing stock, that attracted and fostered a multiracial queer and gender non-conforming community for much of the mid-twentieth century which was simply not present in places like Back Bay and Beacon Hill.

Beacon Hill

Established in 1795, Beacon Hill stands as one of Boston's earliest neighborhoods, situated conveniently near the Massachusetts State House and offering scenic views of Boston Common. Its southern slope quickly became an attractive haven for the city's wealthiest and most elite inhabitants. However, unlike some areas such as Back Bay, Beacon Hill's demographics did not remain completely homogenous.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the northern and western slopes of Beacon Hill became home to a diverse community of working and middle-class African Americans. This area soon emerged as the epicenter of abolition politics in New England. Unfortunately, this presence was relatively short-lived, as many African Americans relocated to the South End, Dorchester, and Roxbury after the Civil War.12

As the twentieth century began, Beacon Hill underwent a significant demographic transformation. Wealthy residents started relocating to Back Bay, which opened the doors for a fresh wave of newcomers, including artists, poets, nonconformists, and notably, gay men. During the 1940s and 1950s, both Beacon Hill and Back Bay became highly desirable neighborhoods for gay men seeking a sense of belonging.

According to Lopez, many gay men found the area's appeal rooted in its convenient proximity to Boston Common, MBTA subway stations, and Scollay Square, which were popular meeting spots for socializing and engaging in intimate relationships among gay men. These accessible locations allowed the gay community to gather and connect more easily, fostering a vibrant social scene within the neighborhood.13

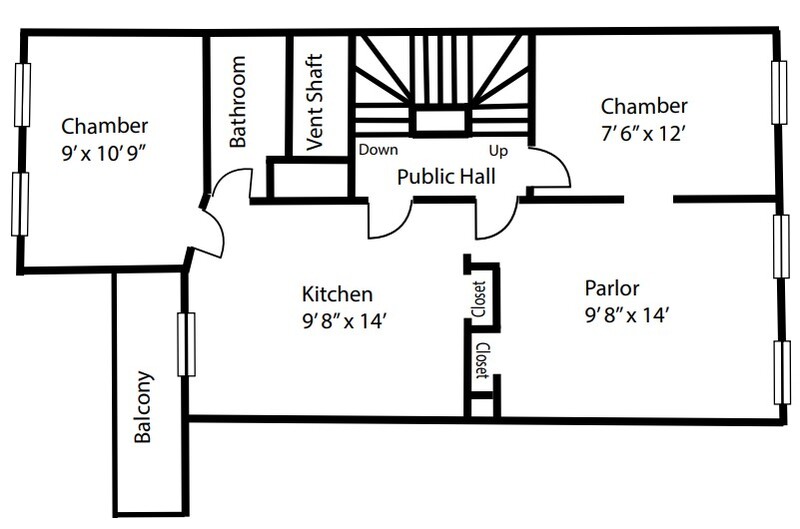

The blueprint above is a typical layout of a home in Beacon Hill. What is shown is a single unit on the second floor. The unit comprises of a bathroom, kitchen, two bedrooms and a parlor. Two to three individuals would have most likely lived in this unit. The third and fourth floors have an identical layout, aside from the first floor which would have a slightly smaller living space due to the front entrance. The total square footage is roughly 475 square feet of space. On average, tenants usually paid anywhere between \$20 a month to \$40.14 Generally, even though many of the homes of Beacon Hill were on the smaller side, the housing of the area would have been nicer and more maintained compared to the dilapidated tenement homes of the South End. Therefore, Beacon Hill fell in the sweet spot between the pricey Back Bay and the more lower-class South End.

After analyzing The Mid-Town Journal, an intriguing revelation came to light. It was observed that all the LGBTQ+ residents mentioned in the journal were gay men, and those few identifiable through the census were exclusively white. Surprisingly, there were no indications of transgender women or black gay men residing in the area or even visiting the neighborhood to socialize with white cis-gender gay men. This suggests that the gay community in Beacon Hill may have been tightly-knit and selective in embracing outsiders. One possible reason for this isolation could be the neighborhood's geography, which physically separated it from the queer and gender non-conforming subcultures of the South End and Back Bay. With Boston Common acting as a barrier between Beacon Hill and Back Bay, and the South End being over a mile away, limited geographic proximity might have hindered significant interactions between these areas and their respective LGBTQ+ communities.

Conclusion

These three Boston neighborhoods provide valuable insights into the experiences of the queer community, shedding light on the distinct circumstances faced by gay men and transwomen based on their place of residence. Back Bay, known for its upscale and expensive living, had highest average rents, much as $100 a month, offering ample living space per person. However, Back Bay was predominantly inhabited by white gay men, with only a few white transwomen. Unfortunately, queer people of color had no representation in this neighborhood.

In contrast, less than a mile away, the South End emerged as the poorest and cheapest neighborhood to live in among the three, characterized by dilapidated housing. Despite this, it boasted the most diverse and multiracial LGBTQ+ community in Boston. Lower-income black and white gay men, along with transgender women, found a home in the South End. On its streets, there was a noticeable queer and transgender presence, with interactions between white and black men and transwomen being evident.

Lastly, Beacon Hill can be described as a neighborhood with a small and close-knit population of white gay men. These individuals couldn't afford the high rents of Back Bay, but earned enough to avoid the lower-quality housing of the South End. The geographic isolation of Beacon Hill may have contributed to the homogeneity of its gay population, resulting in limited diversity within the community.

Notes

- City of Boston. Back Bay/Bay State Road. Carolyn Hughes. Boston Landmarks Commission. Boston: The Environment Department. Online,https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/imce-uploads/2017-07/backbay_baystateroad_brochure.pdf (accessed July 22, 2023).

- "So You Want To Live in the Back Bay?" BostonMagazine.com, accessed July 23, 2023, https://www.bostonmagazine.com/property/2023/01/10/back-bay-neighborhood-guide/.

- "Classified Ad," Daily Boston Globe, July 06, 1951. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/bc.edu?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.bc.edu/historical-newspapers/classified-ad-2-no-title/docview/839552980/se-2.

- United States Department of Labor. Occupational Wage Survey. Bulletin Number 1033. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1951. Online, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/bls/bls_1033_1951.pdf?utm_source=direct_download. (accessed July 23, 2023).

- "South End History, Part I: The "New" South End," South End Historical Society, accessed July 22, 2023, https://www.southendhistoricalsociety.org/south-end-history-part-i-the-new-south-end/.

- "The South End," Global Boston, accessed July 23, 2023, https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/immigrant-places/the-south-end/.

- "The New York Streets: Boston’s First Urban Renewal Project," The West End Museum, accessed July 22, 2023, https://thewestendmuseum.org/exhibits/the-new-york-streets-bostons-first-urban-renewal-project/#:~:text=The%20New%20York%20Streets%20encompassed,Boston%20and%20Albany%20in%201842.

- "Classified Ad," Daily Boston Globe, December 30, 1951. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/bc.edu?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.bc.edu/historical-newspapers/classified-ad-6-no-title/docview/839931047/se-2.

- "Classified Ad," Daily Boston Globe, December 30, 1951. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/bc.edu?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.bc.edu/historical-newspapers/classified-ad-6-no-title/docview/839931047/se-2.

- "From the Great Migration to Boston's Charlestown Navy Yard," National Park Services, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/articles/great-migration-to-charlestown-navy-yard.htm#_ftnref4.

- Paul Finkelman and Cary D. Wintz, eds., Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance: A-J (New York: Routledge, 2004), 501.

- Lopez, The Hub of the Gay Universe, 149.

- National Park Service, "From the Great Migration to Boston's Charlestown Navy Yard."

- Lopez, The Hub of the Gay Universe, 149-51.

- "Classified Ad," Daily Boston Globe, December 29, 1950. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/bc.edu?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.bc.edu/historical-newspapers/classified-ad-1-no-title/docview/839537200/se-2.