By the end of the 1950s and into the 1960s, Americans had been inundated with images of the well known gender nonconforming individuals like Christine Jorgensen and of dire political warnings from conservative politicians who warned of the subversive presence of homosexuals in the federal government. Additionally, the publication of Alfred Kinsey's Sexual Behavior in the Human Male in 1948 was another cultural touchstone that informed Americans that over a third of American men had at least some form of same-sex sexual contact throughout their lives. Kinsey's study became a "media sensation" that was talked about thoroughly in television shows, the press and in Broadway plays. By the end of the decade, "Americans now understood that [queer folks] were everywhere, even if you could not see them."1

As we can see with the graph above, the journal overwhelmingly reported on the deeds of transgender women who made up over 70% of the LGBTQ+ folks mentioned in last six remaining years of The Mid-Town Journal. It appears that the significant uptick in transgender women becoming more a visible subculture in Boston might be due to the conspicuous presence of LGBTQ+ themes and subjects in media throughout the 1950s. For example, The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, was one of the first organizations in America that fought for the rights of homosexuals while The Daughters of Bilitis, founded five years later, focused on the civil rights of gay women.2

Furthermore, beginning in the 1950s, there was a "unparalleled outpouring of representation and discussion about homosexuals" in novels and short stories.3 Queer men and women could now begin to read and see themselves as individuals with complex motivations and queer desires. Trans women like Jorgensen flaunted the front pages of newspapers across the country. Bookshops openly sold queer literature that exposed heterosexuals to queer themes. Kinsey exposed the extensive same-sex sexuality that many American men engaged in.

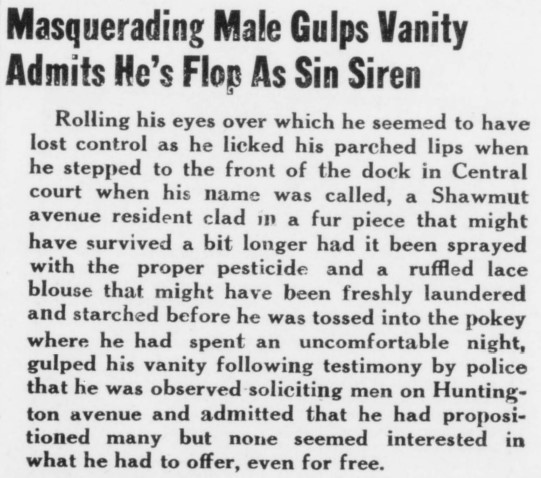

A decade of queer and gender nonconforming men and women emerging from the shadows may have given a confidence boost to the transgender women of Boston. The constant portrayal of transgender women in The Mid-Town Journal should also be considered as a factor that encouraged some trans women to venture out into the public. Though it needs to be acknowledged that the representation of trans women in the journal was negative in that they only were depicted as sex workers or violent vagrants. Shibley's discourse regarding transgender women was contemptuous. Nevertheless, the local media coverage of trans women could have signaled to other trans women that they were not alone in their identities and that there were similar gender nonconforming folks living relatively open lives in the Boston area. If other gender nonconforming folks were walking the streets presenting as women, so could they. The 1960s was a new decade after all and many trans women may have felt a renewed sense of optimism and hope that it was time to emerge from their homes and defiantly stroll the streets presenting as women.

The map above displays the arrest locations that have been recorded in The Mid-Town Journal from 1960 to 1966, the year the journal ceased publication. In many ways the the activities we see that LGBTQ+ folks are being arrested for were largely taking place in the same areas as they did in the 1940s and 1950s. The major difference in the early 1960s was that the police were arresting transgender women on a more frequent basis than they were in the 1940s and 1950s. In this era, we see more transgender women walking the streets late at night soliciting sex from passing motorists.

It is also interesting to note that generally we see little mention of police raiding private parties hosted by gay men or arrests of gay men in secluded parking lots or MBTA bathrooms and lounges. This could indicate that the authorities were less concerned with arresting gay men for their private sexual encounters or that by the early 1960s, the Boston Police Department no longer perceived homosexuality and lesbianism as public nuisances that needed to be policed. Another possible theory considers The Mid-Town Journal itself. Frederick Shibley may have realized that the interests of his readers may have shifted. He spent the better part of twenty years mostly covering the sexual exploits of gay men and women. With the exposure of gay themes and subject matters in other printed media, Shibley could have determined that the readership may be tiring of these types of stories. So, perhaps instead Shibley decided to publicize the escapades of the transgender women of Boston which could have been a more exciting and interesting topic for his readers.

The map above, which shows all of the home addresses from The Mid-Town Journal during the early 1960s, largely mimics the home addresses maps from the 1940s and 1950s. We can see that the Back Bay and the South End remained popular spaces for LGBTQ+ folks to live. In addition, there were several individuals who continued to live out in Roxbury as some did in the 1950s.

It is important highlight what cities and neighborhoods appeared to be the most desirable for queer folks. Then from there, we can examine why they wanted to live in those spaces. The mapping portion of this project did not investigate why these spaces were alluring for queer and gender nonconforming folks to live in for that is outside the scope of this study. But, in order to even address the 'why' problem, we need to first identify where they felt the most comfortable living. Over a 20+ year period, we can conclude that the Back Bay and the South End persisted in being relatively safe and enticing neighborhoods for many queer men and women to live. LGBTQ+ men and women obviously lived in every American city. But, some cities and locations were more alluring than others. Housing affordability or close proximity to other known queer and gender nonconforming individuals may have been possible driving forces that attracted gay men and women to these spaces. Regardless, the maps presented throughout this site have hopefully helped depict the lost queer communities of Boston.

Notes

- Bronski, A Queer History of the United States, 177-8.

- Bronski, A Queer History of the United States, 180-1.

- Bronski, A Queer History of the United States, 183-4