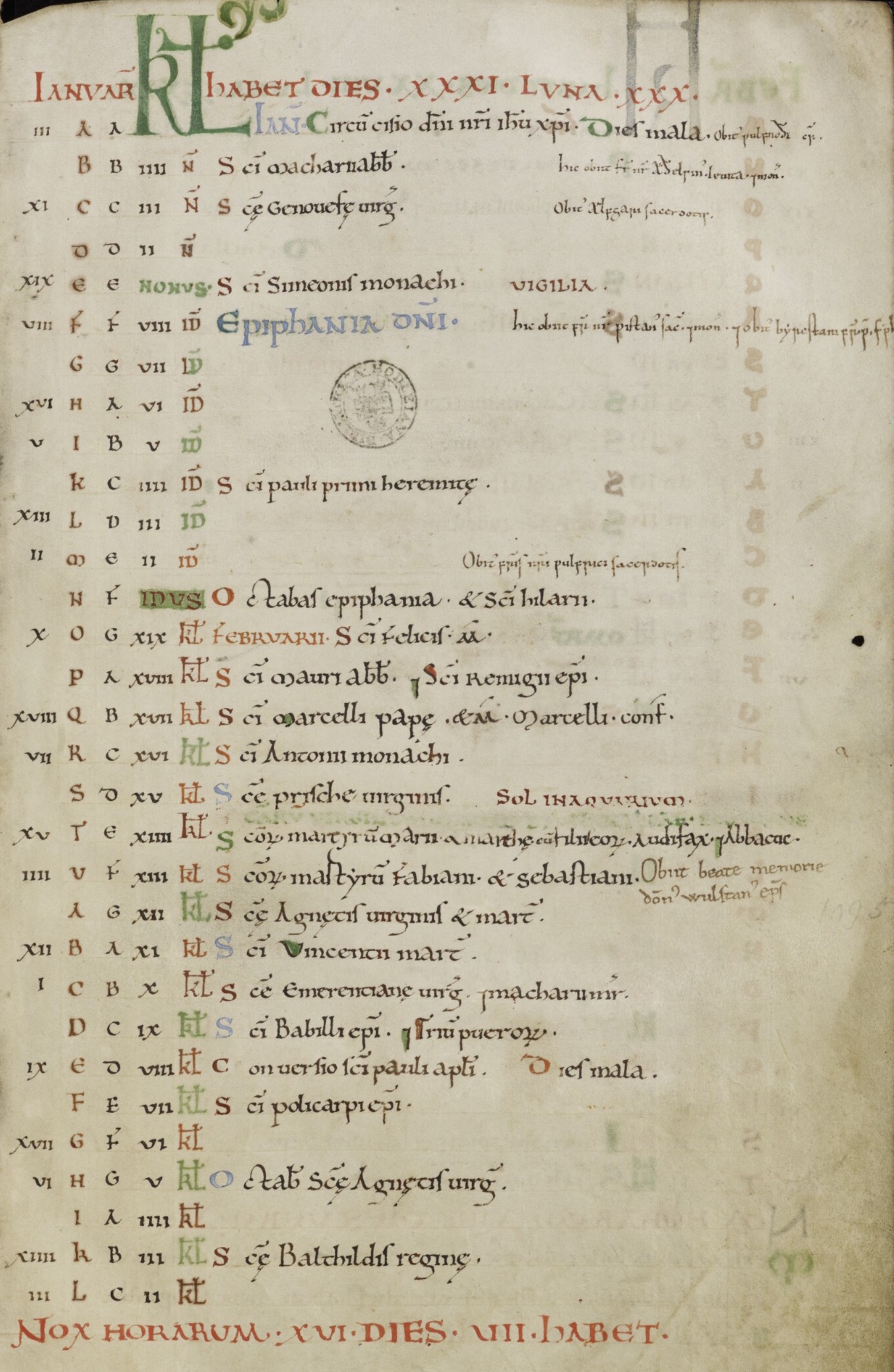

Calendar table for the month of January from Bodleian Library MS Hatton 113 f. iii r. This manuscript also contains some of Ælfric's homilies.| Image courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Calendar table for the month of January from Bodleian Library MS Hatton 113 f. iii r. This manuscript also contains some of Ælfric's homilies.| Image courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Calendars, the way people describe and order time in their life, are social organizations. Different calendars reveal different ways of forming particular cultural identities: an academic institution's year runs from September to May, and time is measured by semesters; governments, on the other hand, may be structured around the fiscal year, which has its own terms and timelines.

Ælfric, a Christian monk in an agrarian society which was a former Roman province, lived within at least three social calendars:

- The seasonal calendar, divided into winter and not-winter in Anglo-Saxon England with the harvest figuring prominently in the year.

- The Roman calendar, divided into twelve months beginning on January 1 and ending on December 31.

- The Christian liturgical calendar, divided into various liturgical seasons and marked by particularly significant feasts.[2]

The Christian liturgical calendar is a combination of sanctoral, fixed feast days for various saints, and temporal, moveable feasts based on the date of Easter. These feasts fit into six seasons: 1) Advent, beginning 4 Sundays before Christmas, 2) the twelve days of Christmas from December 25 to the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6, 3) Ordinary Time from the Epiphany until the beginning of Lent, 4) Lent, beginning 40 days before Easter, 5) Easter, running from the variable date of Easter for 40 days until Pentecost, and 6) Ordinary Time from Pentecost until the start of Advent again.

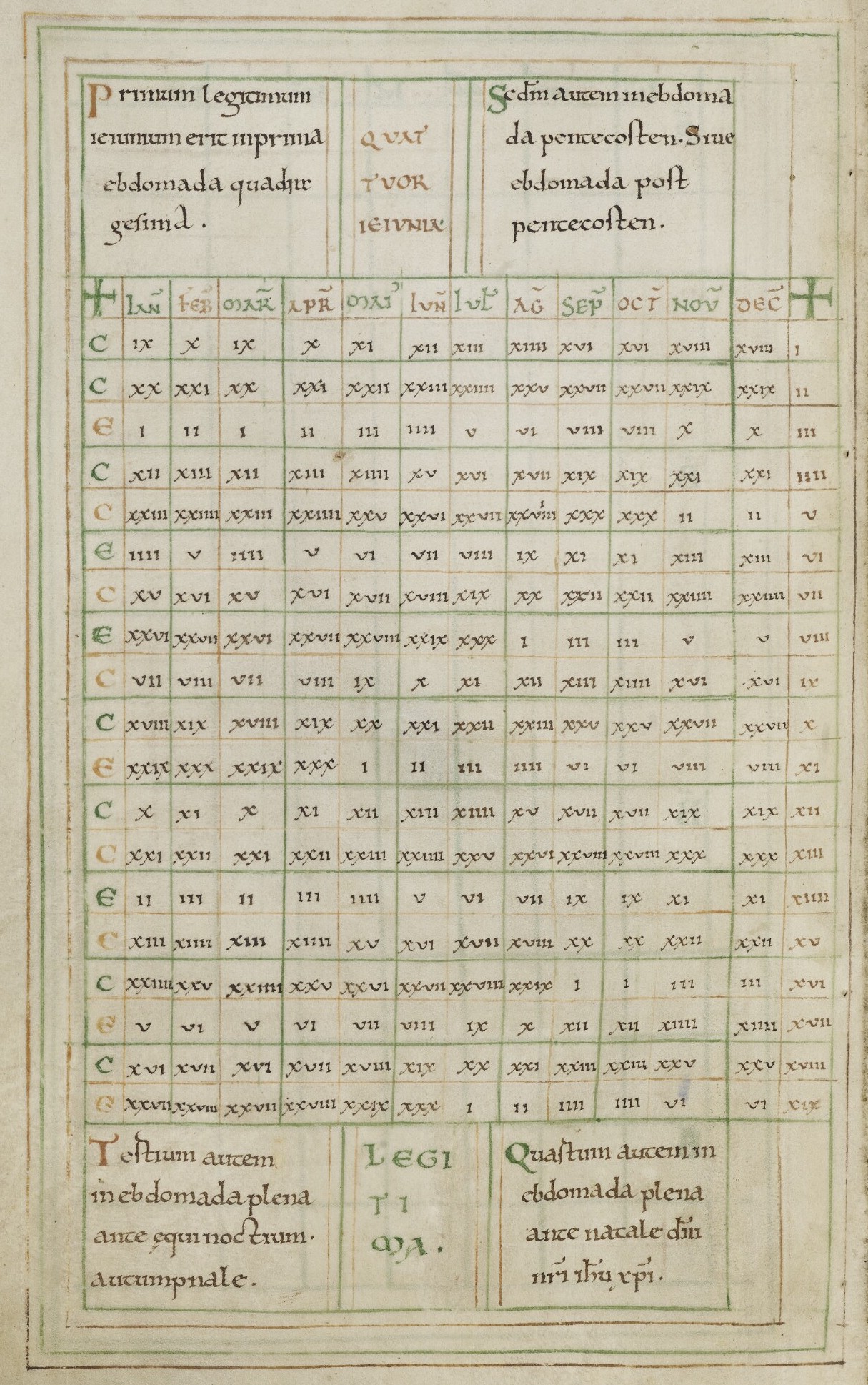

Computistical table of a 19-year lunar cycle showing the age of the moon of the first day of each month from Bodleian Library MS Hatton 113 f. ix v.. This manuscript also contains some of Ælfric's homilies.| Image courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Computistical table of a 19-year lunar cycle showing the age of the moon of the first day of each month from Bodleian Library MS Hatton 113 f. ix v.. This manuscript also contains some of Ælfric's homilies.| Image courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

For Ælfric, the liturgical year defined his sense of time, and his homilies are keyed to these religious feasts. Yet even these religious feasts that Ælfric commemorates with his homilies reveal something about time in early England. "Proportion of Homilies to Liturgical Year" shows how many homilies in Ælfric's first series fall during each liturgical season. The Christmas season, only twelve days in the liturgical year, has five homilies, while the first season of Ordinary Time, which is 35 days long, has only three feasts observed.

The liturgical seasons aren't weighted evenly, and those seasons with the most important feasts have disproportionately more homilies throughout. Christmas and Easter especially are inflated, while Lent and Advent remain relatively proportional.The second season of Ordinary Time, which makes up over half the year, holds less than half of Ælfric's homilies—the front of half of Ælfric's year is liturgically heavier, with more major feasts shaping his sense of time. Independent feasts like Epiphany and Pentecost keep the year turning more quickly through winter and spring, until the year seems almost to move lethargically through the summer and fall.

The "Timeline of Homilies" reflects a handful of gaps between Ælfric's commemorated feasts from January to May, but Ælfric doesn't write a single homily for the month of July and the last half of the year staggers its way back toward Christmas with large windows between the homilies. This movement, fast-spaced and reinvigorated after the high celebration of Christmas then slower, plodding up to Advent, perhaps illustrates the major anticipation Ælfric and his contemporaries would have had for the feasts of the Christmas season, emphasizing Christ's birth as the lifeforce of the Catholic Church, while the inflation of feasts in Eastertide demonstrates Christ's Resurrection as the pinnacle of the year.

Notes

- James Hurt, Ælfric, pp. 22–25.

- See Eleanor Parker's Winters in the World for a thorough, yet easily accessible, journey through the Anglo-Saxon year.