A full understanding of Ælfric's life and works demands a consideration of how the man experienced the spatial and temporal dimensions of his surroundings. Once Ælfric moved to Cerne Abbey, his world became the immediate space around him.

Unfortunately, there is not much physical evidence that remains, and what we do have requires a certain amount of speculation to make sense of the world. All the original buildings of the abbey at Cerne which Ælfric would have occupied have been destroyed. When Henry VIII separated England from the Catholic Church, he dissolved the monasteries of the "old" religion in England and tore down many of their buildings. The oldest structure remaining of Cerne Abbey is a tithe barn dating to the 14th century, 400 years after Ælfric was living.

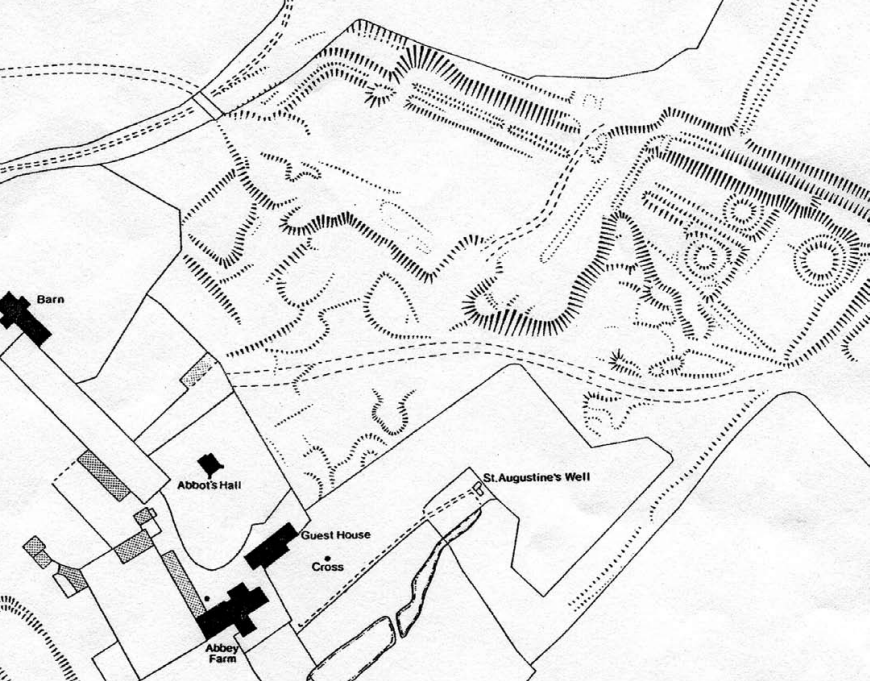

In the map below, the area outlined in red is the location of the extant remains after the dissolution of the monastery in 1539—these buildings, as historically significant as they may be, have no relationship to the world of Ælfric. The area in blue, however, is where the original abbey would have stood during Ælfric's tenure. The only remains from Ælfric's time are the earthworks in the eastern portion of the area in blue, which can also be seen in the top right corner of the diagram next to the map.[1]

These earthworks are likely a kitchen garden, but there has been no excavation done for this region of the monastery. All we have are guesses and raised earth.

Powered by: Esri, Intermap, NASA, NGA, USGS | Esri Community Maps Contributors, Esri UK, Esri, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, GeoTechnologies, Inc, METI/NASA, USGS | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, Microsoft, Facebook, Inc. and its affiliates, Esri Community Maps contributors, Map layer by Esri.

Powered by: Esri, Intermap, NASA, NGA, USGS | Esri Community Maps Contributors, Esri UK, Esri, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, GeoTechnologies, Inc, METI/NASA, USGS | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, Microsoft, Facebook, Inc. and its affiliates, Esri Community Maps contributors, Map layer by Esri.

Diagram of Cerne Abbey today | Courtesy of the Cerne Historical Society, History of the Abbey

Diagram of Cerne Abbey today | Courtesy of the Cerne Historical Society, History of the Abbey

Here, an imaginative approach to Ælfric's environment may prove profitable. As Mary Jones, a local historian of Cerne Abbas, puts it: "[g]oing over the actual familiar ground, as it exists today, seeing the same contours around one, as the men of a thousand years ago could see them, may bring some realization of what life consisted of then, and bring a greater ability to interpret what records are still existing."[2] How might Ælfric have traveled around the abbey, passing under the hills surrounding Cerne and walking through the Wessex landscape?

The trails highlighted in pink in the map above crisscross their way through the Dorset countryside, linking together various sections of the Wessex Ridgeway in southwest England. The Wessex Ridgeway is part of the system of prehistoric walking routes making up the Great Chalk Way, an ancient highway with a history millennia older than Ælfric.[3] Traveling to and from Cerne Abbey, Ælfric likely would followed these footpaths to the larger ridgeways, navigating narrow trails and gazing out on the rolling hillscape.

A view across chalk hills on the path from Cerne Abbas to Minterne Magna | Photograph: Leon Foggitt | The Guardian (2021)

A view across chalk hills on the path from Cerne Abbas to Minterne Magna | Photograph: Leon Foggitt | The Guardian (2021)

As Ælfric wandered the area, making his way carefully along the narrow trails, perhaps he would have passed beneath the feet of the Cerne Abbas Hill Giant, the 180-foot-tall figure carved into the hillside immediately north of the abbey. The Cerne Giant (outlined in yellow on the map above) is Britain's largest and most famous chalk hill figure, very likely constructed in the Late Saxon period when Ælfric was active.[4] Though no one is certain exactly when or why the giant was etched into the face of the hill, archeological evidence indicates that it overlooked the Dorset countryside by the 10th century. Mary Jones' evocative description may help us to imagine what it would be like for Ælfric to see the giant leering from his perch:

The Giant may have dominated the hillscape, a remnant of the pre-Christian England incorporated into the daily imagination of the people. Located barely 600 feet from the north end of Cerne Abbey, the Giant (or other traditions like it) would have figured prominently in Ælfric's mind as an example of the "false beliefs" he was hoping to correct with his homilies.

When John Hutchins compiled his history of Dorset, he recorded a folktale about the origins of the hill figure: "There is a tradition, that a giant, who resided here-about in former ages, the pest and terror of the adjacent country, having made an excursion into Blackmore, and regaled himself with several sheep, retired to this hill and lay down to sleep. The country people seized this opportunity, pinioned him down, and killed him, and then traced out the dimensions of his body, to perpetuate his memory."[6]

Was it this story Ælfric had in mind when he wrote that some of the earlier pagans "had faith in dead giants, and lifted up costly idols to them, and said that they were gods because of the great strength which they had"?[7] The proximity of Cerne Abbey to such a hill figure as the Giant may reveal the immediacy of Ælfric's concerns in his Catholic homilies.

Notes

- "Abbey History," Cerne Historical Society, p. 1.

- Mary Jones, Cerne Abbas: The Story of a Dorset Village, p. 14.

- Wessex Ridgeway, Long Distance Walkers Association; Ben Johnson, "The Ridgeway," Historic UK.

- "Cerne Giant," National Trust.

- Jones, Cerne Abbas, pp. 42–49.

- John Hutchins, The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset, p. 293.

- Ælfric, "Feast of Saints Peter and Paul," 5.