The Late 10th Century

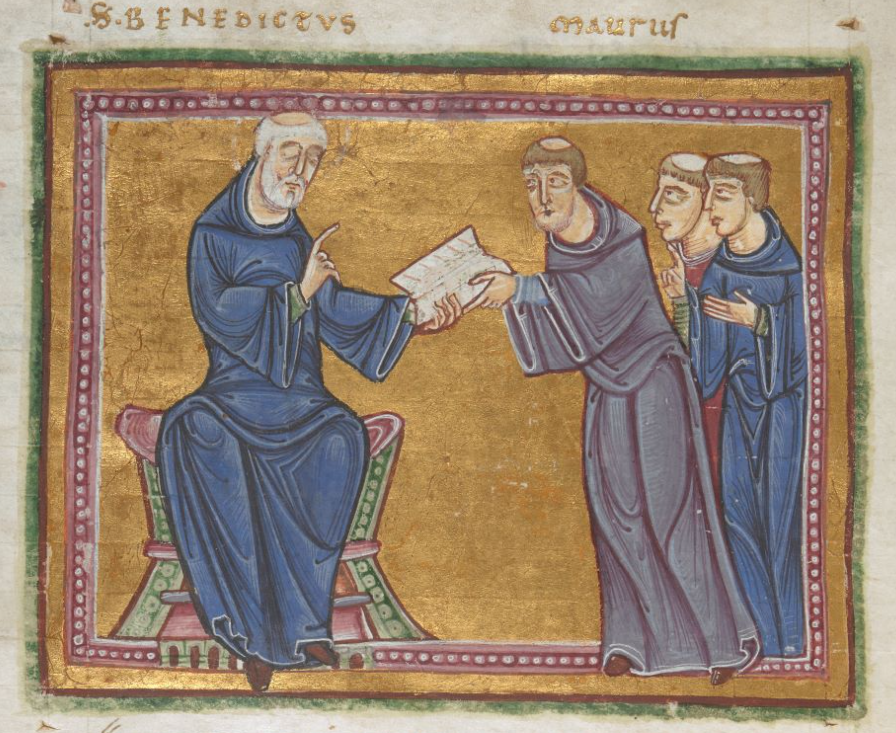

St. Benedict delivering his rule to the monks of his order | Image courtesy of the British Library, London, Add MS 16979, f. 21v

St. Benedict delivering his rule to the monks of his order | Image courtesy of the British Library, London, Add MS 16979, f. 21v

King Alfred the Great (c. 848–899) had secured southern England from the Danish invaders by the mid-890s and became a precursor for the restoration of the English Church (cf. Alfred’s translations mentioned in Ælfric’s Preface 1). In the subsequent decades of relative peace, the English bishops Dunstan, Oswald, and Æthelwold initiated their monastic reforms. While the Benedictine monks of old had been beholden to strict vows of religious life, Æthelwold found the secular priests (not associated with particular vows) to be “given to gluttony and drunkenness”.[1] Backed by King Edgar (c. 944–975) and Dunstan, Æthelwold commanded those who refused to take monastic vows to leave. This Benedictine Reform, which began in Winchester, spread across the island.

The reformers were not, however, interested only in a stricter monastic lifestyle. The efforts of Æthelwold and others allowed art, literature, and learning to flourish again in England, despite the looming threat of the Danes. Monks living in monasteries dedicated themselves to reading and writing, and many of them demonstrated a keen interest in educating the regular lay people who lived near them.[2] Yet England was haunted by the Danes, and constant anxiety underpinned much of the literature of the 10th century. English priests and monks wanted to prepare the people for what they understood as the end of the world. Many of these fears proved to be well-founded, as Danish raids began again in the final years of the 10th century.

Shaped by a reinvigorated literary period as a result of the Benedictine Reform and by the near-apocalyptic fears caused by ongoing Danish invasions, Ælfric became one of the most prolific early English writers. His homilies in particular reveal his talent for teaching, translating, and interpreting for lay and religious audiences alike.

Ælfric's Life

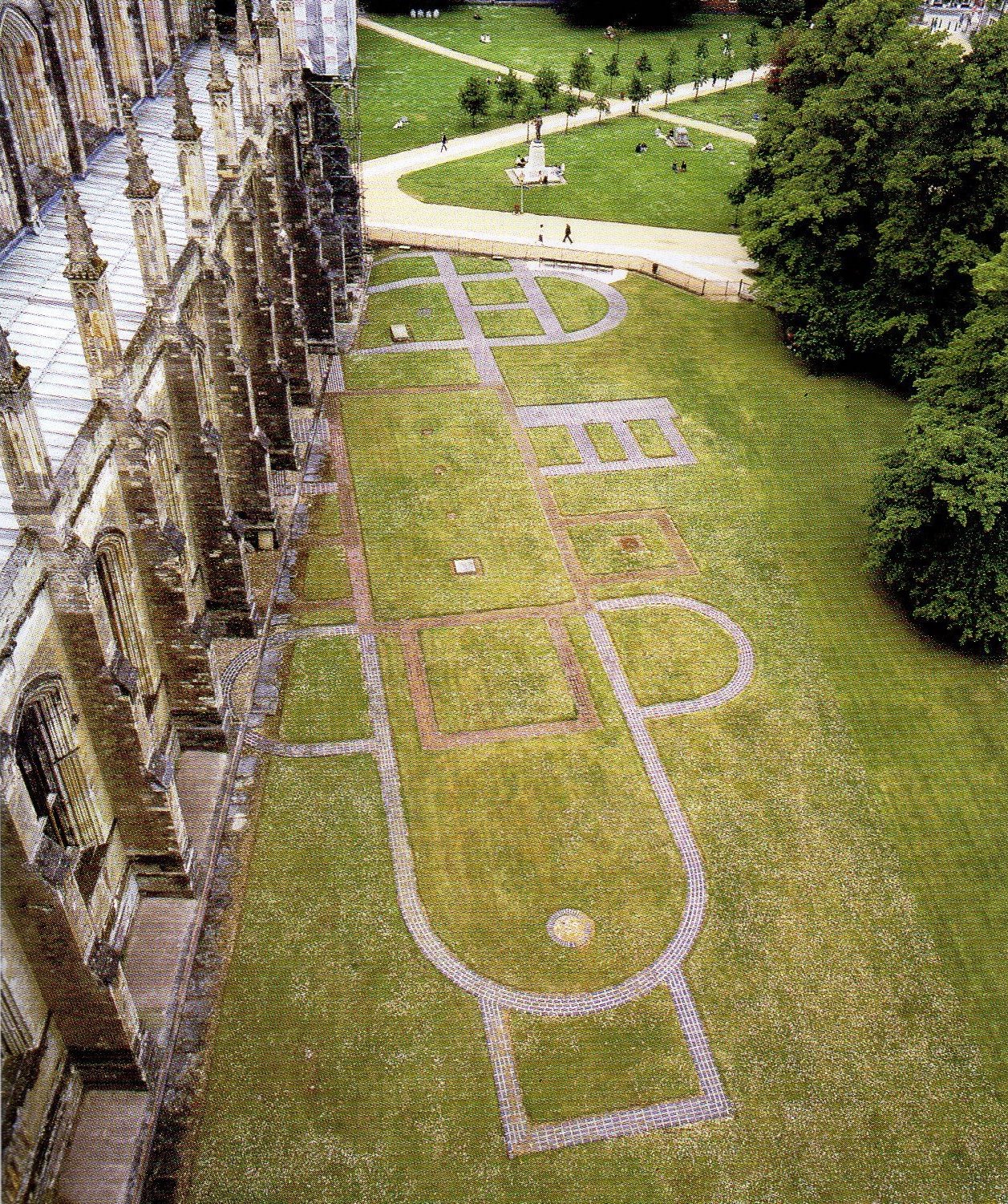

Tiled outline of the Old Minster of Winchester, likely the place where Ælfric was taught | Jon Cannon, Cathedral: The Great English Cathedrals and the World that Made Them, 600–1540, Constable, 2007, p. 45

Tiled outline of the Old Minster of Winchester, likely the place where Ælfric was taught | Jon Cannon, Cathedral: The Great English Cathedrals and the World that Made Them, 600–1540, Constable, 2007, p. 45

Ælfric himself tells us that he spent many years at Æthelwold’s school at Winchester, and since we know that Æthelwold died in 984, it’s safe to assume that Ælfric entered that monastic schooling sometime in the 970s.

After his first years at Cerne, Ælfric got it in his mind to write two series of Catholic Homilies (and perhaps he was specifically asked to by his benefactor Æthelmær, the founder of the abbey). The first was written in 989, followed quickly by the second in 992. The order of the homilies, which are arranged according the feast days throughout the Church’s liturgical calendar, support this timeline; the dates for each of the feasts which Ælfric lists align with those feastdates in the respective years.

Ælfric remained a priest at Cerne until he was appointed as the abbot of the monastery at Eynsham in 1005. There he remained until his death in about 1010. Ælfric's work over the course of his lifetime has caused historians to assign him many titles, but perhaps his most important (and maybe the one he'd have liked best) is Ælfric the Homilist.

Notes

- James Hurt, Ælfric, p. 20.

- Ibid, p. 21.

- Joyce Hill, "Ælfric: His Life and Works," A Companion to Ælfric, pp. 35–65.