Origins

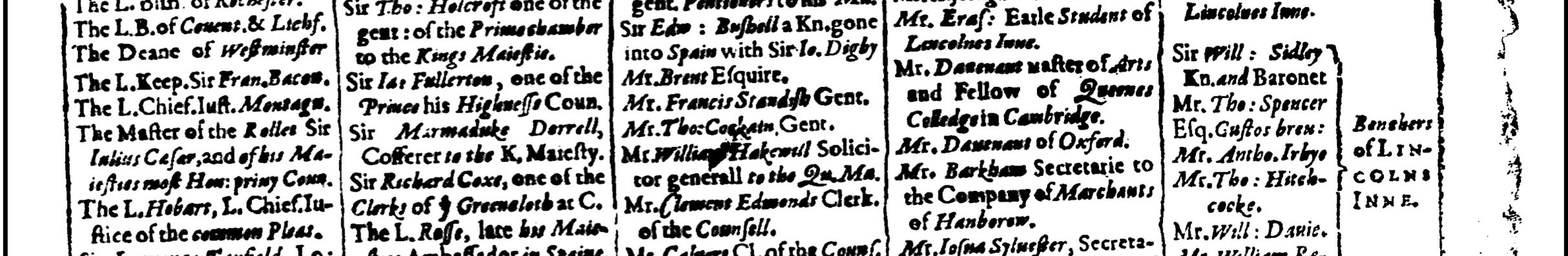

Publication by subscription arose in seventeenth-century England as a way to offset the financial risks of printing large, expensive, and scholarly books. Although Minsheu’s A Guide into Tongues (1617) is the first book known to have been published by this method, it was not until the post-civil-war era of the 1650s that other authors began collecting subscriptions, and truly not until the 1720s that it became well-established. Sarah Clapp has identified fifty-four works published through subscription between 1617 and 1688, and an additional thirty-three between 1689-97, although most of these did not include lists of their subscribers' names.1 Some authors expressly collected subscriptions to pay for illustrated plate engravings, as John Ogilby did for his illustrated translations of Virgil’s works (1654) and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (1660, 1665). In these instances, subscribers’ names and their coat of arms were incorporated into each plate illustration, rather than in a separate list.

Typically, the process began with an author or bookseller publishing a proposal to subscribers, in which they advertised the book in question, describing its topic, size, and cost. With multi-volume works, there was often a discount if subscribers would pay for all volumes at once. The proposal would state the “undertakers” of the work, those individuals who would collect subscribers’ money and be responsible for distributing the work when printed. Proposals might also explicitly state that subscribers would have their names printed in the finished work, and request subscribers to state their titles or locations to include in the list.

As Clapp has noted, book subscriptions can be understood as part of a larger economic trend developing in the seventeenth century towards collective and cooperative commercial activities, similar to the joint-stock or subscription models that trading and insurance companies began using in this century.2 Like these other ventures, publication by subscription did not always work: proposals exist for books that never reached the press, and for multi-volume works that only printed the first volume. Conversely, some authors printed their regrets at not being able to include subscribers’ names in the final editions or their frustration with subscribers who had yet to pay in full. Still, publication by subscription allowed some authors the chance to publish works that, in Minsheu's words, would otherwise be "dead at the presse for want of mony."3

Notes

- Sarah L. C. Clapp,“The Beginnings of Subscription Publication in the Seventeenth Century,” Modern Philology 29 (1931): 205.

- Clapp, "The Beginnings of Subscription Publication," 202.

- John Minsheu, A catalogue and true note of the names of such persons which (vpon good liking they haue to the worke being a great helpe to memorie) haue receaued the etymologicall dictionarie of XI languages ... from the handes of Maister Minsheu the author ..., London: 1617.