Initial Findings

Early modern England was a status-conscious society, a reality that is apparent in subscription lists. It was in the best interests of all to highlight one’s status. Subscribers functioned as mini-patrons, testifying to the worth of the book, so authors and publishers encouraged subscribers to include their titles when subscribing as forms of endorsement. Subscription lists also distinguished their members, offering them public prominence and free advertisement of their accomplishments. The desire to show proper reverence to illustrious subscribers caused some authors anxiety, as John Minsheu fretted in 1617 in the preface to his list, "If in setting downe these Names, there hath not beene observed the respect due to the Rankes and qualityes of persons, Hee Intreats the Reader to understand that he hath not done it out of neglect of the regard he owes to them, but only to follow the order he used in delivery of the Bookes to them, which was not according to their degrees, but promiscuously as they tooke them."1

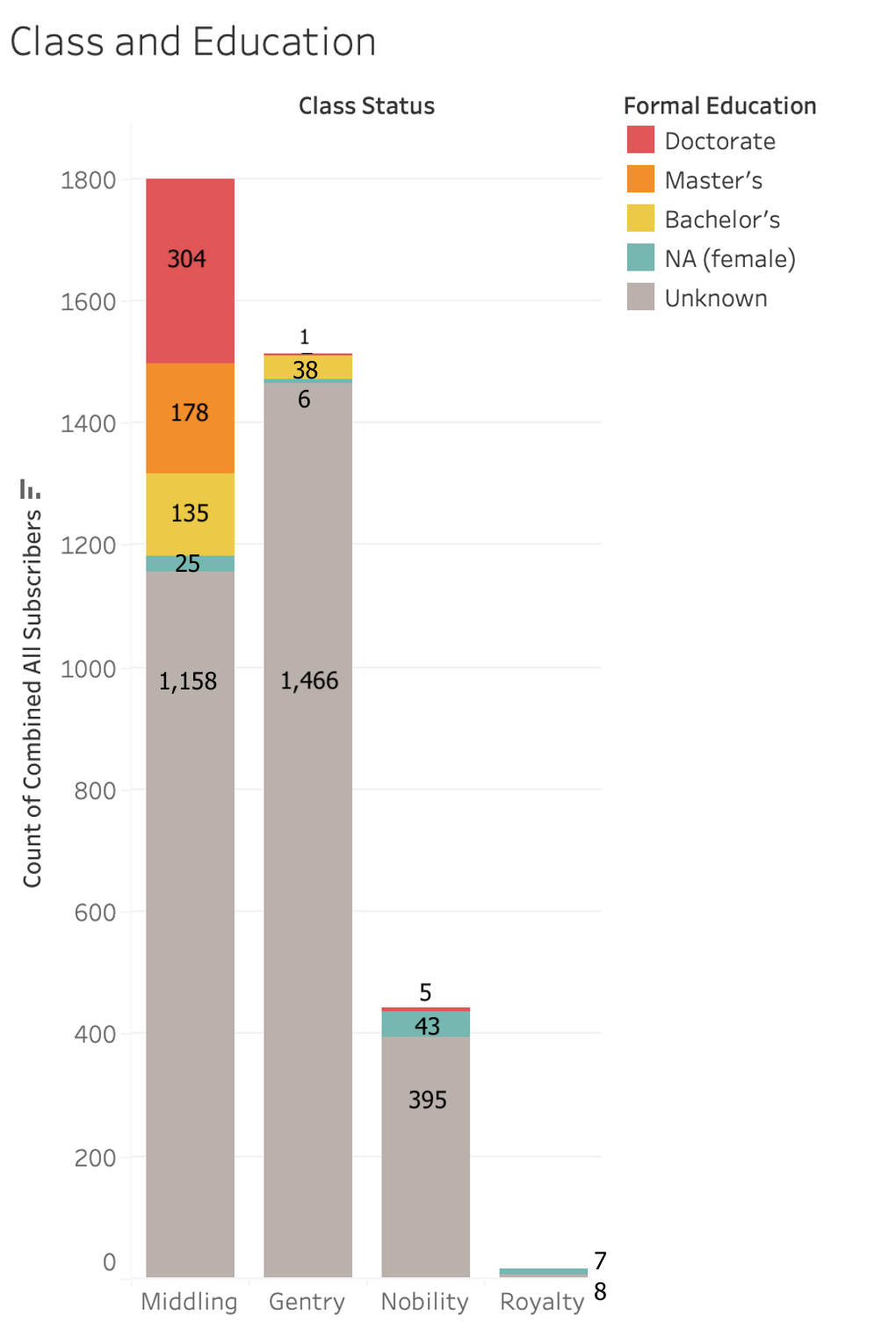

But for men without a noble title or even the ability to claim gentry status, education was the means for highlighting their achievements. Although by the end of the seventeenth century a stint at university had become common for members of the gentry and nobility and many would take a degree, very few subscribers from these classes bothered to state their accomplishments in subscription lists. The only noblemen to do so were either bishops with doctorates in divinity or men like The Honorable Dr. John Mountague [Montagu], who as the fourth son of an earl was highly unlikely to inherit his father’s title. The only gentry members who stated a degree directly, rather than indicating it by stating their profession, were subscribers to Athenae Oxoniensis, which was a catalog of Oxford alumni. In such a context, stating one’s academic credentials might have more worth.

The predominance of academic markers amongst middling subscribers, rather than the gentry, suggests that advanced educations were most valuable to those who lacked familial or monetary markers of social status.

Chart made with Tableau.

Notes

- John Minsheu, A catalogue and true note of the names of such persons which (vpon good liking they haue to the worke being a great helpe to memorie) haue receaued the etymologicall dictionarie of XI languages ... from the handes of Maister Minsheu the author..., London: 1617.