Brief History of Public Housing

Public housing in the United States was very much a conception of the New Deal era. The first public housing development in the United States was built in 1935 in Atlanta, Georgia. Soon after, Boston followed suit by building the Old Harbor Village in South Boston which opened in 1938. Despite its nearly eighty-year history, the Old Harbor Village still exists to this day, with necessary updates and renovations. After WW2, there was an immediate demand for affordable housing, and Boston took the lead with public housing per capita. The city wanted to house its low-income and working-class families to remove urban blight and foster a burgeoning middle class - regardless of race. From the late 1930s into the 1950s, we see cities across America using public housing as a way to transform their cities into places of slums into efficient housing for all who required housing.

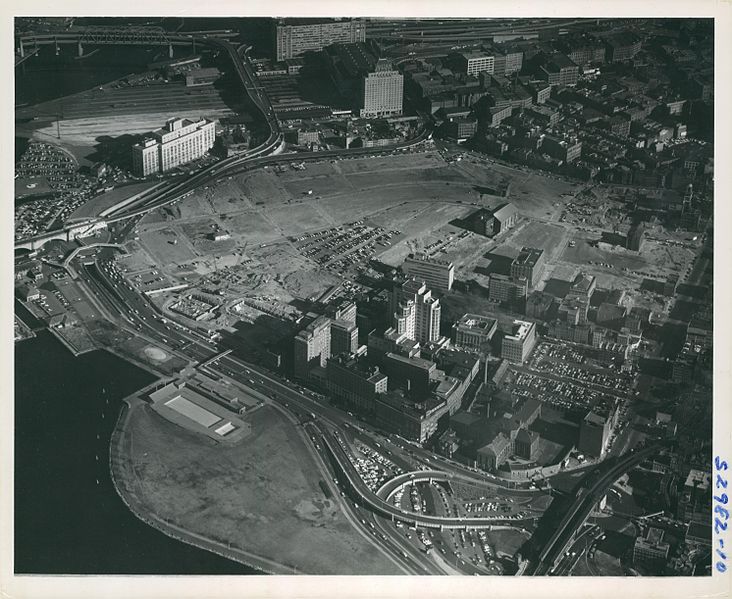

"New Boston"

Urban renewal and "New Boston" have often been hailed as bringing much needed revitalization to this historic but aging city, but the intentional consequences, much like any colonial quest, comes from the lack of land to develop upon. Instead of developing new land, it is often the next-best resort to develop already existing land. There are typically two ways of doing so - the space to which you would create is already vacant, or, you take undesirable land and make it vacant. A number of books and research has been done on urban planning in Boston and “New Boston.”

Liz Cohen’s articulation of urban renewal as an extension of New Deal liberalism, in her book, Saving America’s Cities, is incredibly apt - just like the New Deal excluded many Black workers and helped cultivate a specific vision of the middle class, urban renewal was perpetuating the same vision through different means. While the goals might have been good-intentioned, it is hard to pose that as useful when this renewal has perpetuated a system that keeps people unable to move up in society and create generational wealth. My contribution in this project aims to look past the intentions of city planners and the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), the Boston Housing Authority (BHA), or UMass-Boston Board of Trustees. It situates itself in the growing literature of the direct shortcomings for New Deal liberalism that led to the urban crisis; not the latter existing in spite of it.

Racial Tensions

The racial climate in Boston existed prior to the busing crisis which shot Boston to national attention for less than ideal reasons. South Boston had been the location for many working-class Bostonians, many of Irish heritage. Boston's racial and ethnic demographic changed dramatically in the early to mid-20th century. The Second Great Migration launched a new, vibrant Black population in Boston. Moreover, the 1960s featured high numbers of immigration from the Caribbean and brought many Hispanic immigrants to Boston. The sudden transition to a global city sparked tension between its residents.

In December 1974, at the beginning of the busing crisis, the Boston Globe featured an article marking the Mary McCormack Housing Project in South Boston as the "worst" - and yet the media representation of Columbia Point was more consistent and more unflattering.1 The racial implications which divide Columbia Point and the Mary McCormack housing unit are more than just housing squabble. Boston's public housing was notoriously practicing de facto segregation. At the same time, Columbia Point's residents were dealing with a racially vitriolic climate. The busing scandal of the early 1970s added to the racial divisions and desire for mainitign the racial hierarchy of the city.

While de facto segregation worked in neighborhoods, it did not always extend to public housing. But soon, it would also spread to public housing. And even with the de facto segregation, the violence and retaliation against Black neighbors was intense and immense. In the early 1960s, the Boston Globe continually picked up stories of Black violence against white people, but rarely mentioned the violence that Black residents had been relentlessly subjected to over the years. In some publications, mostly by the Bay State Banner which focused on a Black perspective, the residents expressed their frustration over the lack of coverage or understanding of the constant violence they faced. Instead, Black violence was vilified as exemplary of urban crime and desitutition.

Notes

- Anne Kirchheimer, “Vandalism at housing project in South Boston city's worst,” Boston Globe, December 23, 1974.